"The Irishman": A Country for Old Men | Review

NOTE: This review discusses some of the major historical events depicted in The Irishman. Some may consider them spoilers.

It’s finally here.

After spending over a decade mired in development hell, Martin Scorsese has made his long-gestating adaptation of I Heard You Paint Houses. The 2004 non-fiction book, written by Charles Brandt, charts the life and career of Frank Sheeran, an enforcer for the Bufalino crime family in northeastern Pennsylvania who rose up the ranks of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters to become one of its most prominent members.

More importantly, Sheeran was allegedly a cold-blooded killer who carried out much of the family’s dirty work throughout his career, and purportedly carried out the slaying of former Teamster boss Jimmy Hoffa, whose disappearance still remains officially unsolved as of this writing.

From the outset, The Irishman (titled "I Heard You Paint Houses" in the film) is obsessed with death in a way none of Scorsese’s other crime films have been. Just about every character dies, either of natural or unnatural causes. The ones we don’t see die get their eventual cause of death (nearly always violent) described via a text card when we first meet them. This is Scorsese’s Unforgiven, a referendum not only of the movies he’s made in the past, but of the characters he’s arguably glorified in films that are largely considered among the greatest in American cinematic history.

Steven Zaillian’s (Schindler’s List) screenplay is sprawling, covering not only Sheeran’s life but that of the Teamsters and various leaders throughout the middle of the 20th century. At times, the film almost plays like Forrest Gump, watching Sheeran have tangential interactions with some of the most infamous people and events in recent American history. A large portion of the second hour follows the Teamsters’ and organized crime’s involvement in getting John F. Kennedy elected and, when certain promises weren’t kept, subsequently assassinated.

The veracity of this material will likely forever be questioned, but the dramatization of it is riveting. Not only is The Irishman a stunning conclusion to the series of crime/gangster movies that Scorsese has made throughout his career (Mean Streets, Goodfellas, Casino, The Departed), it also makes for a fine companion piece to films like The Good Shepherd and JFK. Those who know their Cold War history will find much of interest here.

In fact, the veracity of the entire movie will be heavily disputed by those who see it. The book itself has been attacked by those in organized crime and law enforcement alike as being pure fiction. The specter of truth vs. fiction is a common one during awards season, where films "inspired by true events" get vilified for not adhering to each and every established historical fact. But true or not, Scorsese is not interested in creating a historical documentary. Sheeran is representative of larger thematic undertakings that Scorsese wants to pursue. Those looking for the facts can get in line; law enforcement has been searching for decades.

Performance-wise, Pacino is fine. Working with Scorsese for the first time, he delivers a largely measured but appropriately forceful performance that turns Hoffa into a surprisingly lovable and almost cuddly character. There are times when the blustery Pacino of his post-Scent of a Woman career bursts out, and these moments are often played for laughs. But Pacino finds the beating heart of a man who knew how to unite people until, suddenly, he didn’t. The insecurity of losing the Teamsters (Hoffa often refers to it as “my union”) quickly gives way to a steely determination to win it back at any cost. This tragic determination is played beautifully by Pacino, resulting in his best performance (outside of HBO movies) since he won the Academy Award over 25 years ago.

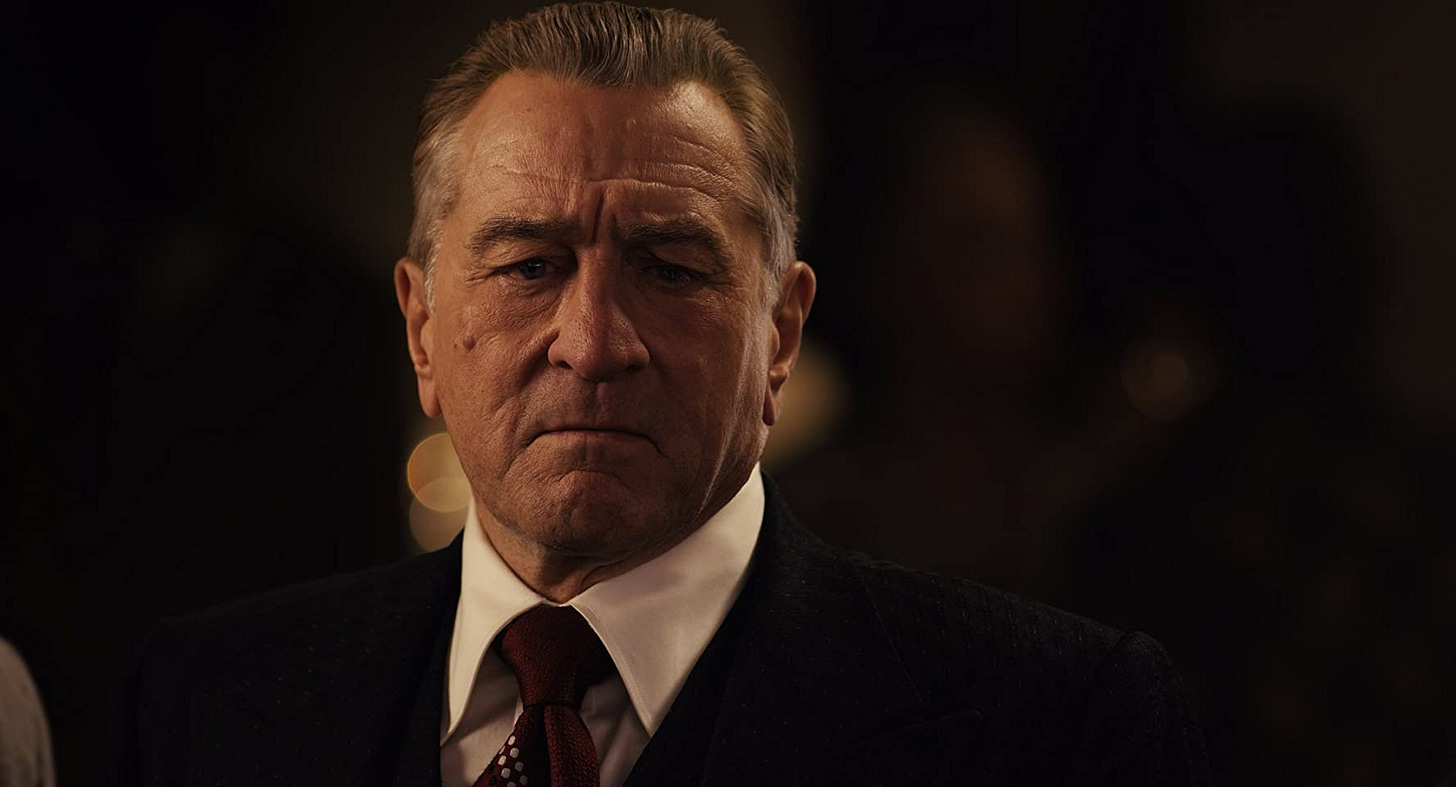

Present in just about every scene, De Niro towers over the movie as Sheeran. It’s his best work since at least Silver Linings Playbook, maybe even as far back as the last time he worked with Scorsese – 1995’s Casino. For two-thirds of the movie, he turns in a stoic, low-key performance. But a transformation happens in the final hour, when a profound melancholy, regret, and ultimately, resignation sets in for Sheeran about the life he’s lived. De Niro handles the material powerfully, and if he gets nominated for an Academy Award, it will be for his work in this final hour.

And then there’s Joe Pesci, who quietly turns in the film’s best performance. We’re used to seeing Pesci play explosive characters like Tommy DeVito in Goodfellas or Nicky Santoro in Casino. But in a movie that boasts fellow firebrand Pacino, Pesci goes the other way, playing Russell Bufalino as a quiet, internalized man. Outwardly calm and tranquil, Bufalino is capable of meting out great violence when necessary. He never partakes in it himself, but blood is on his hands throughout the movie. The dichotomy of this character – the fatherly warmth he displays towards Sheeran, at one point calling him the son he could never have, juxtaposed against the types of jobs and the danger that he consistently puts Sheeran in – is meaty stuff, and Pesci tears into it in a way we haven’t quite seen from him before.

It's a joy to see Pesci reunite with De Niro, and although he only gets a single one-on-one scene with Pacino, both actors make the most of it. Reportedly, Pesci had to be coaxed out of semi-retirement to take on this part. Thankfully, he did. If any actor deserves to win an Oscar for their work here, it’s Pesci.

Aside from the three leads, the rest of the cast is capable, fitting seamlessly into the world crafted by Scorsese and his collaborators. Big names like Harvey Keitel (as infamous Philly crime boss Angelo Bruno), Bobby Cannavale (as Felix DeTullio), Jack Huston (as Robert Kennedy), and even Ray Romano (as Bill Buffalino, cousin of Pesci’s Russell) all work in perfect unison. At times, the film plays like a game of “Spot the Soprano.” There’s probably a fun drinking game someone could make out of it.

Much has been made of the lack of female representation in the movie; Scorsese’s mob movies have often been like this, but even within that context, strong female characters dominate films like Casino and have wide-ranging character and narrative relevance in films like The Departed. Anna Paquin’s character (Sheeran’s daughter Peggy) is shown growing up as a child irrevocably scarred by knowing about her father’s line of work. Thematically, the film is largely about family and the choice of one family over another. It’s about a man taking stock of his life and what he will – or won’t – leave behind. Peggy is, therefore, less a character than a personification of that theme; her silence is deafening whenever she’s on screen, and the tragedy is how long it takes for Sheeran to realize that he’s lost her.

Speaking of the final act -- it's interesting to see a Scorsese movie so devoid of religion in its imagery or thematic underpinning. We're shown baptisms as Sheeran's daughters are born, and Kennedy's Catholicism is given passing references. But they're superficial, included mainly to show the passage of time, the growing closeness between the Sheerans and Bufalinos, or the growing fury of Hoffa at a President he helped get elected but by whom he's now being persecuted via an over-zealous Department of Justice.

It isn't until the final half-hour that religion takes center-stage. In Amadeus-like fashion, a wheelchair-bound Sheeran speaks with a local priest about guilt, regret, sorrow, and what the presence or absence of his emotions means for him and his soul. It might as well be Scorsese having these conversations with himself. The man who made Taxi Driver, a movie that inspired a Presidential assassination attempt, is interrogating the legacy that his films are leaving behind. It's extraordinary stuff, and when the film's final shot lingers, we realize that there are no easy answers to his questions. Seeing this movie less than two months after Joker, it's likely too soon to have those answers anyway.

There's also a fascinating meta-commentary about the real Frank Sheeran. As mentioned, his claims to killing Hoffa and even Crazy Joe Gallo (which is covered in the film) have been extensively refuted over the years. With the film largely being about legacy and what damaged men leave behind, it's interesting to ponder what the real Sheeran must've been thinking towards the end of his life, taking credit for several murders in order to secure himself a place in the annals of American criminal history and, now, Hollywood's history, too.

De-ageing effects look surprisingly good except for two things: Pesci’s early scenes look a bit off (too shiny, ironically), and De Niro’s piercing blue eyes never quite look natural. Pacino fares best in this regard; it’s almost impossible to tell if he’s even been de-aged at all. The only caveat is that, while the technology is able to make these men look younger, their physicality never quite matches the youth of their visage. De Niro always moves like an older man, even when he’s supposed to be in his late-30s or early-40s.

Rodrigo Prieto’s lensing is strong, if not exactly spectacular. Thelma Schoonmaker’s editing is typically incredible, with the nearly three-and-a-half-hour runtime mostly flying by. When things begin to slow down towards the end, it’s for a reason, as Scorsese takes his time with a dramatic tragic event and the ensuing fallout. This is some of the most stunning work of his career.

As mentioned, the VFX work is largely excellent, and the make-up department obviously plays a large part in the success of the de-ageing effects. Production and costume design are excellent, and will likely merit serious Oscar consideration. Robbie Robertson’s music curation is fine. I also would not be surprised to see The Irishman nominated for Sound Editing.

You may have noticed that I didn't assign a star rating to this review - this was deliberate. Much as The Irishman took so long to make, and takes so long to watch, it needs time to digest. This is an incredible piece of work from one of the greatest directors of all time. Scorsese may have been dragged down into the mud recently with the great Marty vs. Marvel beef of 2019 (see Ryley's excellent dissection of that brouhaha), but The Irishman is a forceful reminder of why artists like Scorsese need to be taken seriously. As much as I love the Marvel Cinematic Universe and superhero movies at-large, there will never be one that ascends to the heights of Scorsese at the top of his game.

And there likely will not be a better movie than The Irishman in 2019.