Why I Hate That I Love Spider-Man: No Way Home

A spoiler filled rant overanalyzing something I love

I love Spider-Man. I have foundational memories about Spider-Man when it comes to my deep and abiding love for superheroes. On weekends when my dad was in town, we would watch the 90s Spider-Man cartoon, along with the OG Speed Racer, on Saturday mornings together. The first comic book I ever bought was a reprint of The Amazing Spider-Man #1. But perhaps most extraordinary of all, I still remember seeing the legendary pre-9/11 Spider-Man trailer before Jurassic Park III. I have spent a lot of my life and devoted a lot of space in my brain to Spider-Man. It’s an unusual choice I’ve made with my life, but here we are.

I only say all this to say that I love Spider-Man. And Spider-Man: No Way Home is a celebration of Spider-Man. And that’s fun! And not just a celebration of the MCU Spider-Man. But a celebration of weird Steve Ditko art, Spider-Man memes, and—of course—all the movies and that came before, which is a ton of fun.

And indeed, No Way Home is an overwhelming critical and financial success that is primed to be the next movie Hollywood learns all the wrong lessons from. Because while it’s a fun, grand Spider-Man celebration, it isn’t a good movie. And to understand why Hollywood is about to make all the wrong decisions now, we need to understand what bad choices got us here first.

Marvel Movies Before The MCU

One thing I’ve always thought has gone must unappreciated about the Marvel Cinematic Universe is just how much of an underdog Marvel was going into Iron Man. In the age of billion-dollar Disney-produced blockbusters, it’s hard to remember that Iron Man was an independent $140M film distributed by Paramount. And it was not guaranteed to succeed.

The comic book business can be tough kids. That risk came from the fact that Marvel had sold off the rights to all their most well-known characters. Marvel had to build a movie universe with Thor and Groot because they’d sold the rights to Daredevil, The X-Men, and The Fantastic Four. And to stay afloat, the Marvel Entertainment Group sold off the rights to any character with a Q Score higher than one.

But selling movie rights can only get you so far. And in 1996, Marvel Comics filed for bankruptcy. This led to a very contentious legal battle, which resulted in a Toy Biz take over of Marvel Comics. How and why Toy Biz is a whole other thing but for now, let’s leave it at toys make money and contracts get signed.

And by way of a very complicated legal decision, Toy Biz also reclaimed the rights to all those film rights they had sold off. And then—get this—they sold them again! But under more restrictive agreements that meant Toy Biz execs, Ike Perlmutter (who sucks) and Avi Arad had much more say in how Marvel movies were made.

If this all sounds nebulous and political to you, let me put it in unambiguous movie terms. The Ike Perlmutter/Avi Arad era of Marvel movies? We’re talking

Ben Affleck in Daredevil (2003)

Fantastic Four (2005)

Man Thing (2005)

Ghost Rider (2007)

You get the kind of movies I’m talking about. They’re those early 2000s, pre-MCU superhero movies that hadn’t figured the formula out yet, and were widely experimental as a result. Sometimes Galactus was a cloud. Sometimes Nic Cage was damning his enemies to the literal Christian Hell. There wasn’t a lot of consistency. And in this era, we got Sam Rami’s Spider-Man 2 (2003) and Spider-Man 3 (2007)1.

The Rami/Maguire Years

There have been many think pieces revisiting past Spider-Man movies going into No Way Home. But I haven’t seen much talk about how revisiting the original Spider-Man Trilogy is an insane experience. Sam Raimi’s time in the Spider-Man director’s chair ran from 2002–2007. And it exists like a mosquito trapped in pre-MCU amber.

Spider-Man 3 is a weird mess that deserves more public defense than it gets, but the first two are beloved films. And let’s be clear: deservedly so. They’re campy and tragic and scary all at the same time. Toby Maguire was at the center of a fantastic cast. The visual effects were like nothing we’d ever seen before. And thanks to producer Laura Ziskin, they’re 100% comic book movies. They strike the crucial balance between Ang Lee’s perfect film, Hulk (2003), and the superhero phobic X-Men (2000), which, strangely, doesn’t seem to have been directed by anyone.

The way Spider-Man and Spider-Man 2 engage with the idea of Peter Parker is incredible. Raimi somehow manages to outfit his villains with all the camp of drag queens without sacrificing any of their menace. William Defoe, dressed up like a Power Ranger villain, cackling from the bak of his hoverboard is I-C-O-N-I-C. Remember when he screamed at Aunt May to finish the Lord’s Prayer? Wild.

And the deep, personal examination of Alfred Molina’s Doctor Otto Octavos is tragic. They’re both beautiful, patient pieces of art that hadn’t yet discovered the “superhero movie formula.” And I love that about them. They’re getting everything right without getting anything right. It’s a wild thing to admit, but the best MCU movies have only ever flitted up against the emotionality of those early Raimi films.

Something that’s even less talked about is that Kevin Feige, yes that Kevin Feige, was an Associate Producer on the Sam Raimi Spider-Man movies. But it’s wild to think back now and imagine The Godfather of the Marvel Cinematic Universe, watching the birth of the modern superhero movie, scribbling down notes on what worked and what didn’t. Knowing he didn’t have the power to steer the ship but knowing that one day he would. And knowing he’d need a plan when that day came. He seems like a plan guy, right?

The Garfield/Webb Years

After that came the Amazing Spider-Man franchise, which saw Andrew Garfield take his turn under the mask. This period in Spider-Man film history was dominated by a conflict between director Marc Webb and Avi Arad.

Feige’s control over the MCU had significantly downsized Arad’s role at Marvel Studios. Arad’s portfolio became Spider Films. But boy was he enthusiastic about his charge. Wild rumors swirled online about the behind-the-scenes politics at Sony between Arad and Webb. Arad’s plan for a Sinister Six movie seemed to depend on the failure of Amazing Spider-Man 22. There was even talk of Arad pitching an Aunt May spy flick. It was a weird time to be a Spider-Man fan, defined mainly by an unrelenting freefall in quality.

Indeed, the Sony Spider-Man movies had become so inconsistent that Marvel finally demanded creative input. They wanted someone to be at the table suggesting edits, even if Sony ignored those suggestions. And who do you think got to be ignored? That’s right—our sweet boy Kevin Feige, who by this time was running a superhero movie empire at Disney. Leaked emails from the Sony hack show Feigie advising Sony against some of the worst parts of the Garfield Amazing Spider-Man franchise3.

By the infamous Sony hack, Spider-Man producer Amy Pascal was being (unjustly) run out on a rail. And her Hail Mary was “the Sony/Marvel deal.” And while the deal is complex, the fundamentals are pretty simple: Since Sony had licensed the Spider-Man film rights from Avi Arad, they had shit the bed on not one (1) but two (2) different Spider-Man film franchises. Meanwhile, Feige had built a machine that turned superhero IP into money with the MCU. And in the wake of the Disney acquisition, any doubt regarding Marvel’s complete market dominance had been quashed. The Sony/Marvel deal was a match made in heaven. Sony got good Spider-Man movies. And Marvel got to welcome Spider-Man home.

Spider-Man’s Homecoming

And I can honestly say that Tom Holland’s time as Peter Parker, directed by John Watts, has been a unique delight. Feige learned all the right lessons from the Spider-Man franchises that came before.

Sony burned too much time walking us through the spider bite, so Marvel took all of that off-screen. Sam Raimi and Marc Webb had spent all their time showing us Spider-Man swinging around New York. So Feige and Watts took him out of Manhattan and showed us what Spider-Man looked like in Prague, Paris, and London. Instead of spending time showing us how he learned to swing from webs (again), the MCU Spider-Man movies gave us a Peter Parker who had to grapple with his fear of heights on top of the Washington Monument.

In short, Marvel was banking on the fact that we already knew who Spider-Man was. When we were first introduced to Peter Parker in Captain America: Civil War (2016), Spider-Man’s legacy on film is doing a lot of work. When a 15-year-old Peter Parker says to Tony Stark, “When you can do the things I do, but you don’t, and then the bad things happen, they happen because of you,” we as an audience heard, “With great power comes great responsibility.” We instantly knew who this kid was. He was Spider-Man. How could we not recognize him?

And Feige & Co. rode that recognition as far as they could. Specifically, two movies and three contractually obliged appearances in non-Spider-Man movies. And that was apparently all the confidence Marvel had in Kevin Feigie’s bold new vision for Spider-Man. Because in 2018, Sony asked a daring new question: What if there were like… a lot of different Spider-Men. But they were all hanging out together in the same place?

Let’s Get Into The Spider-Verse

Spider-Man: Into The Spider-Verse is an incredible movie that I love a lot. There’s a lot to be said about the weird creation of the quote-un-quote Spider-Verse by comics writer Dan Slott (who I also love a lot). And even more to be said about Miles Morales, created by Brian Michael Bendis, whose existence in the Marvel Ultimate Universe always seemed like an unspoken barrier that would keep him out of the movies. So when Miles showed up in an incredible movie that honored the comics history of Spider-Man while digging into the mythos created by a fantastic Spider-Man writer, it was a tidal shift in what Spider-Man movies could be.

It was no surprise that the success of Spider-Man: Into The Spider-Verse impacted the plot of Spider-Man No Way Home. But it’s almost dumbfounding to see how No Way Home took almost every wrong lesson away from Into The Spider-Verse. And it seemed to set up even more bad lessons for more people to learn.

This Multiverse is Madness

In some ways, the 2019 novel coronavirus couldn’t have happened at a better time for Marvel. The Infinity Saga was finally over. The franchise that had spent 12 years teasing what comes next was finally at the end of their story. The fact that none of us could safely visit a movie theater for two years didn’t have to touch the Teflon franchise. They could hold the movies they had already made until theaters were safe again and then go back to printing money.

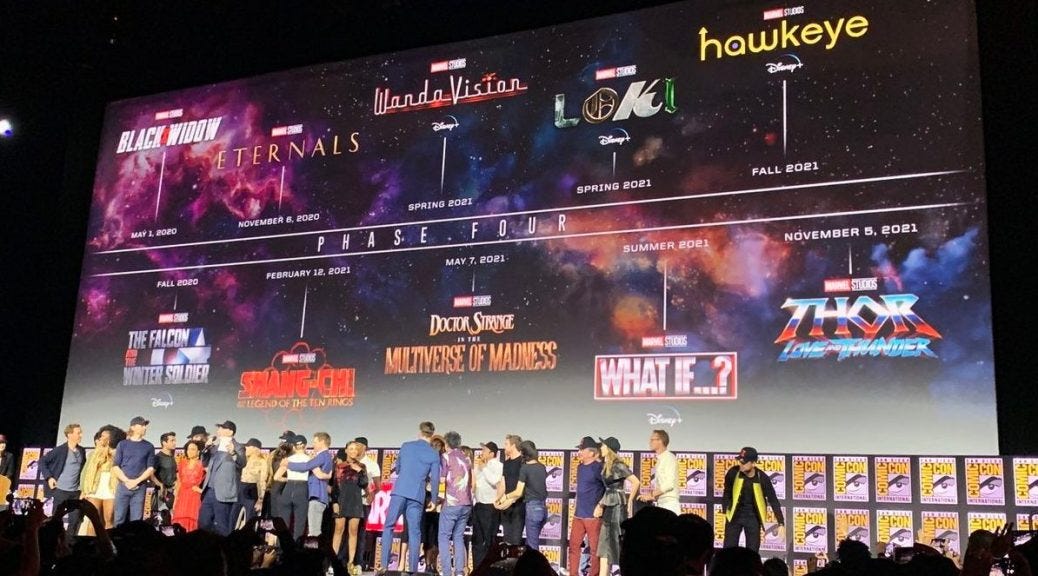

According to that original lineup, Spider-Man: No Way Home was positioned as the Avengers of Phase 4. 2021 was set to be The Year Of The Multiverse. In that lineup, No Way Home would’ve been the final payoff, pulling together three different Spider-Mans for the exciting final showdown — whose stakes are entirely Multiverse based. WandaVision’s climactic finale would’ve hinted at the Multiverse and led directly into Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness, in which Wanda and Strange would explore the Multiverse together. Then Loki would’ve established the firm rules, and What If…? would’ve explored the dark corners.

Instead, Spider-Man: No Way Home is a mess. On the one hand, it has to serve as a capper on the Tom Holland Spider-Man trilogy. But on the other, it wants to serve the Multiverse lords as demanded by Into the Spider-Verse and Multiverse of Madness. And maybe that’s too much for one movie to accomplish. But without the setup of Doctor Strange, three Spider-Men feels more like a cash grab than a thematic payoff.

Kevin Feige’s new vision for what Spider-Man goes out the window after No Way Home’s first act. After that, the movie nosedives straight into the worst impulses of Avi Arad’s reign. But what seems to be the unavoidable conclusion of Spider-Man: No Way Home is that bringing in the Avi Arad Era characters meant bringing in the Avi Arad Era styling.

Despite the complete lack of need, the movie rehashes the spider bite and Fridges Aunt May so she can say “Great Power/Great Responsibility.” The climax of the film is all the genetic web-swinging around New York City scaffolding at night, the visual curse that the Holland/Watts Spider-Man finally overcame. Perhaps most unjustly, the first Spider-Man series, which had managed to avoid throwing women off buildings for Spider-Man to save, went ahead and threw Zendya off a building for Andrew Garfield to rescue. Yes, we gained some of the best Spider Villains and got to resolve the ghosts of Parkers past. But what did it cost?4

The Wrong Lessons

If it is so apparent that Spider-Man: No Way Home wouldn’t work outside of the original Phase 4 order, then why was it released early? Only the people who make those decisions know for sure. But the Spider-Man producers certainly seem interested in keeping Sony happy right now. And that’s to say nothing of the overly verbose credit block dedicated to Producer Avi Arad in the credits of No Way Home.

THE FILMMAKERS WOULD LIKE TO GRATEFULLY ACKNOWLEDGE THE ORIGINAL TRUE BELIEVER, AVI ARAD, WHOSE VISION LED THE WAY TO BRINGING THESE ICONIC CHARACTERS TO THE SCREEN.

Of course, Marvel would want to keep Sony happy. Sony’s spent the last few years building up a stable of Spider-adjacent characters, including Jared Leto’s upcoming turn in Mobius and Tom Hardy’s Venom series. If Sony decided to take their ball and go home, they’d be able to pop Peter Parker right into their movies and likely see massive financial gains for it.

And there’s the problem. The single most important thing in Hollywood right now is intellectual property rights. And that overwhelming truth has spilled over into the movies themselves, like art imitating life imitating art. Ready Player One was an early suggestion that movies were headed that way. Space Jam: A New Legacy and Matrix: Resurrections have already proved it. And the upcoming Flash movie will feature both Ben Affleck and Michael Keaton’s Batmans.

But that problem isn’t just a Warner Bros. problem. In the same way, Into The Spider-Verse seemed to suggest that people were interested in many Spider-Men. And the critical and box office success of No Way Home will be all studio executives to confirm that theory. But they did it without any of the risk-taking of Rami, the enthusiasm of Webb, or the style of Into The Spider-Verse.

And at the end of the day, that’s the disappointment. I would have no problem with Thor: Love and Thunder giving us three Thors. But I don’t just want three Thors for the sake of three Thors. I want it as an exciting choice that comments on the larger franchise and furthers the movie on its own. Disney is a cinematic powerhouse, the likes of which have never been seen in Hollywood. That’s just an inescapable fact at this point. The choices they make determine the future of the industry.

And with great power comes great responsibility.

Weirdly not Spider-Man (implied 1). That was produced under a previous agreement. Seriously, it’s insane to think how much very serious lawyers get paid to think about Spider-Man.

Which is just wild.

When Avi Arad wants to make a bad movie, he makes a lousy movie, goddamnit! No matter what superhero movie geniuses are advising him not to.

Everything.